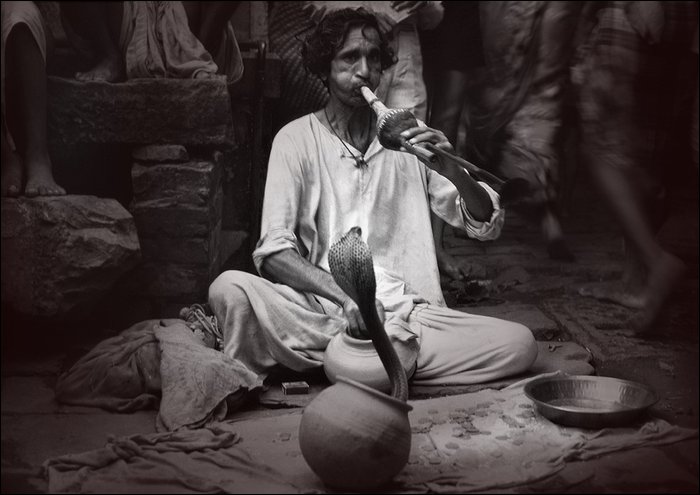

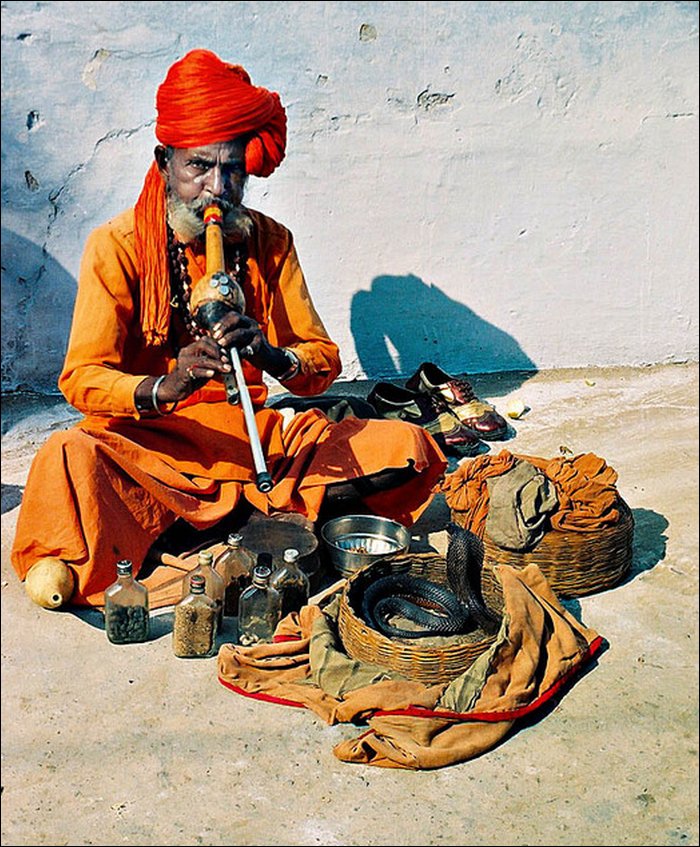

Snake charming is the practice of hypnotising a snake by playing an instrument. A typical performance may also include handling the snakes or performing other seemingly dangerous acts, as well as other street performance staples, like juggling and sleight of hand. The practice is most common in India, though other Asian nations such as Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Malaysia are also home to performers, as are the North African countries of Egypt,Morocco and Tunisia.

Ancient Egypt was home to one form of snake charming, though the practice as it exists today likely arose in India. It eventually spread throughout Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. Despite a sort of golden age in the 20th century, snake charming is today in danger of dying out. This is due to a variety of factors, chief among them the recent enforcement of a 1972 law in India banning ownership of serpents. In retaliation, snake charmers have organised in recent years, protesting the loss of their only means of livelihood, and the government has made some overtures to them.

Many snake charmers live a wandering existence, visiting towns and villages on market days and during festivals. With a few rare exceptions, however, they typically make every effort to keep themselves from harm’s way. For one, the charmer typically sits out of biting range, and his animal is sluggish and reluctant to attack anyway. More drastic means of protection include removing the creature’s fangs or venom glands, or even sewing the snake’s mouth shut. The most popular species are those native to the snake charmer’s home region, typically various kinds of cobras, though vipers and other types are also used.

The earliest evidence for snake charming comes from Ancient Egyptian sources. Charmers there mainly acted as magicians and healers. As literate and high-status men, part of their studies involved learning the various types of snake, the gods to whom they were sacred, and how to treat those who were bitten by the reptiles. Entertainment was also part of their repertoire, and they knew how to handle the animals and charm them for their patrons.

Snake charming as it exists today probably originated in India. Hinduism has long held serpents to be sacred; the animals are related to theNagas, and many gods are pictured under the protection of the cobra. Indians thus considered snake charmers to be holy men who were influenced by the gods. The earliest snake charmers were likely traditional healers by trade. As part of their training, they learned to treat snake bites. Many also learned proper snake handling techniques, and people called on them to remove serpents from their homes. Baba Gulabgir (or Gulabgarnath) became their Guru, since his legend states that he taught people to revere the reptiles, not fear them.[citation needed] The practice eventually spread to nearby regions, ultimately reaching North Africa and Southeast Asia. The early 20th century proved something of a golden age for snake charmers. Governments promoted the practice to draw tourism, and snake charmers were often sent overseas to perform at cultural festivals and for private patrons. In addition, the charmers provided a valuable source of snake venom for creating antivenins.

Today, only about one million snake charmers remain in India; theirs is a dying profession. One reason for this is the rise of cable television; nature documentaries have extinguished much of the fear and revulsion once felt toward the animals and thus demystified the snake charmer. In addition, many people have less spare time than they once did, especially children, who in previous decades could watch a charmer all day with no commitments to school. Animal-rights groups have also made an impact by decrying what they deem to be the abuse of a number of endangered species. Another factor is urbanisation and deforestation, which have made the snakes upon which the charmers rely increasingly rare. This has in turn given rise to the single most important reason snake charming is declining, at least in India: It is no longer legal.

India passed the Wildlife Protection Act in 1972. The law originally aimed at preventing the export of snakeskins, introducing a seven-year prison term for owning or selling of the creatures. Beginning in the late 1990s, however, animal-rights groups convinced the government to enforce the law with regard to snake charmers as well. As a result, the charmers were forced to move their performances to less-travelled areas such as small villages, or else to pay hefty bribes when caught by police officers. The trade is hardly a profitable one anymore, and many practitioners must supplement their income bybegging, scavenging, or working as day labourers. Children of snake charmers increasingly decide to leave the profession to pursue higher-paying work, and many fathers do not try to make them reconsider. Modern Indians often view snake charmers as little more than beggars.

In recent years, however, the snake charmers have struck back. In 2003, for example, hundreds of them gathered at the temple of Charkhi Dadri in Haryana to bring international attention to their plight. In December of the following year, a group of snake charmers actually stormed the legislature of the Indian state of Orissa with their demands, all the while brandishing their animals. The Indian government and various animal-rights groups have now acknowledged the problem. One suggestion is to train the performers to be snake caretakers and educators. In return, they could sell their traditional medicines as souvenirs. Another proposal would try to focus attention on the snake charmer’s music; the charmer would be like other street musicians. The Indian government has also begun allowing a limited number of snake charmers to perform at specified tourist sites.

Snake charmers typically walk the streets holding their serpents in baskets or pots hanging from a bamboo pole slung over the shoulder. Charmers cover these containers with cloths between performances. Dress in India, Pakistan and neighbouring countries is generally the same: long hair, a white turban, earrings, and necklaces of shells or beads. Once the performer finds a satisfactory location to set up, he sets his pots and baskets about him (often with the help of a team of assistants who may be his apprentices) and sits cross-legged on the ground in front of a closed pot or basket. He removes the lid, then begins playing a flute-like instrument made from a gourd, known as a been or pungi. As if drawn by the tune, a snake eventually emerges from the container; if a cobra, it may even extend its hood.

The first task a would-be snake charmer must tackle is to get a snake. Traditionally, this is done by going out into the wilderness and capturing one. This task is not too difficult, as most South Asian and North African snakes tend to be slow movers. The exercise also teaches the hunter how to handle the wild reptiles. Today, however, more and more charmers buy their animals from snake dealers. A typical charmer takes in about seven animals per year.

The exact species of serpents used varies by region. In India, the Indian cobra is preferred, though some charmers may also use Russell’s vipers. Indian and Burmese pythons, and even mangrove snakes are also encountered, though they are not as popular. In North Africa, the Egyptian cobra, puff adder, carpet viper and horned desert viper are commonly feature in performances.

Except for the pythons, all of these species are highly venomous. At home, snake charmers keep their animals in containers such as baskets, boxes, pots, or sacks. They must then train the creatures before bringing them out into public. For those charmers who do not de-fang their pets, this may include introducing the snake to a hard object similar to the pungi. The snake supposedly learns that striking the object only causes pain.

For safety, North African snake charmers typically stitch closed the mouth of their performing snakes, leaving just enough opening for the animal to be able to move its tongue in and out. Since the members of the audience in that region typically believe that the snake’s ability to deliver venomous bites comes from its tongue, rather than fangs, the public remains satisfied watching the snakes’ tongues flickering through the remaining opening. The downside for the snakes is that they pretty soon die of starvation or mouth infection, and have to be replaced by freshly-caught specimens.

Snake charming is typically an inherited profession. Most would-be charmers thus begin learning the practice at a young age from their fathers. In 2007 a viral video made headlines about an infant who was playing with a defanged cobra. Part of this is due to India’s caste system; as members of the Sapera or Sapuakela castes, snake charmers have little other choice of profession. In fact, entire settlements of snake charmers and their families exist in some parts of India and neighbouring countries. In Bangladesh, snake charmers are typically members of the Bedey ethnic group. They tend to live by rivers and use them to boat to different towns on market days and during festivals.

North African charmers usually set up in open-air markets and souks for their performances. In coastal resort towns and near major tourist destinations one can see snake charmers catering to the tourist market, but in most of the region they perform for the local audiences; an important part of their income comes from selling pamphlets containing various magic spells (in particular, of course, against snake bites).

In previous eras, snake charming was often the charmer’s only source of income. This is less true today, as many charmers also scavenge, scrounge, sell items such as amulets and jewelry, or perform at private parties to make ends meet. Snake charmers are often regarded as traditional healers and magicians, as well, especially in rural areas. These charmers concoct and sell all manner of potions and unguents that purportedly do anything from curing the common cold to raising the dead. They also act as a sort of pest control, as villagers and city-dwellers alike call on them to rid homes of snakes (though some accuse snake charmers of releasing their own animals in order to receive the fee for simply catching them again).

Information and image sources:

Information and image sources: